You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘principal component analysis’ tag.

Recent news of James Watson’s auction of his Nobel Prize medal has unearthed a very unpleasant memory for me.

In March 2004 I attended an invitation-only genomics meeting at the famed Banbury Center at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. I had heard legendary stories about Banbury, and have to admit I felt honored and excited when I received the invitation. There were rumors that sometimes James Watson himself would attend meetings. The emails I received explaining the secretive policies of the Center only added to the allure. I felt that I had received an invitation to the genomics equivalent of Skull and Bones.

Although Watson did not end up attending the meeting, my high expectations were met when he did decide to drop in on dinner one evening at Robertson house. Without warning he seated himself at my table. I was in awe. The table was round with seating for six, and Honest Jim sat down right across from me. He spoke incessantly throughout dinner and we listened. Sadly though, most of the time he was spewing racist and misogynistic hate. I remember him asking rhetorically “who would want to adopt an Irish kid?” (followed by a tirade against the Irish that I later saw repeated in the news) and he made a point to disparage Rosalind Franklin referring to her derogatorily as “that woman”. No one at the table (myself included) said a word. I deeply regret that.

One of Watson’s obsessions has been to “improve” the “imperfect human” via human germline engineering. This is disturbing on many many levels. First, there is the fact that for years Watson presided over Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory which actually has a history as a center for eugenics. Then there are the numerous disparaging remarks by Watson about everyone who is not exactly like him, leaving little doubt about who he imagines the “perfect human” to be. But leaving aside creepy feelings… could he be right? Is the “perfect human” an American from Chicago of mixed Scottish/Irish ancestry? Should we look forward to a world filled with Watsons? I have recently undertaken a thought experiment along these lines that I describe below. The result of the experiment is dedicated to James Watson on the occasion of his unbirthday today.

Introduction

SNPedia is an open database of 59,593 SNPs and their associations. A SNP entry includes fields for “magnitude” (a subjective measure of significance on a scale of 0–10) and “repute” (good or bad), and allele classifications for many diseases and medical conditions. For example, the entry for a SNP (rs1799971) that associates with alcohol cravings describes the “normal” and “bad” alleles. In addition to associating with phenotypes, SNPs can also associate with populations. For example, as seen in the Geography of Genetic Variants Browser, rs1799971 allele frequencies vary greatly among Africans, Europeans and Asians. If the genotype of an individual is known at many SNPs, it is therefore possible to guess where they are from: in the case of rs1799971 someone who is A:A is a lot more likely to be African than Japanese, and with many SNPs the probabilities can narrow the location of an individual to a very specific geographic location. This is the principle behind the application of principal component analysis (PCA) to the study of populations. Together, SNPedia and PCA therefore provide a path to determining where a “perfect human” might be from:

- Create a “perfect human” in silico by setting the alleles at all SNPs so that they are “good”.

- Add the “perfect human” to a panel of genotyped individuals from across a variety of populations and perform PCA to reveal the location and population of origin of the individual.

Results

After restricting the SNP set from SNPedia to those with green painted alleles, i.e. “good”, there are 4967 SNPs with which to construct the “perfect human” (available for download here).

A dataset of genotyped individuals can be obtain from 1000 genomes including Africans, (indigenous) Americans, East Asians and Europeans.

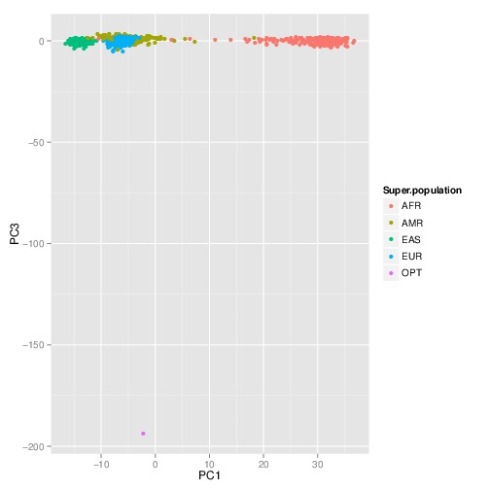

The PCA plot (1st and 2nd components) showing all the individuals together with the “perfect human” (in pink; see arrow) is shown below:

The nearest neighbor to the “perfect human” is HG00737, a female who is… Puerto Rican. One might imagine that such a person already existed, maybe Yuiza, the only female Taino Cacique (chief) in Puerto Rico’s history:

But as the 3rd principal component shows, reifying the “perfect human” is a misleading undertaking:

Here the “perfect human” is revealed to be decidedly non-human. This is not surprising, and it reflects the fact that the alleles of the “perfect human” place it as significant outlier to the human population. In fact, this is even more evident in the case of the “worst human”, namely the individual that has the “bad” alleles at every SNPs. A projection of that individual onto any combination of principal components shows them to be far removed from any actual human. The best visualization appears in the projection onto the 2nd and 3rd principal components, where they appear as a clear outlier (point labeled DYS), and diametrically opposite to Africans:

The fact that the “worst human” does not project well onto any of the principal components whereas the “perfect human” does is not hard to understand from basic population genetics principles. It is an interesting exercise that I leave to the reader.

Conclusion

The fact that the “perfect human” is Puerto Rican makes a lot of sense. Since many disease SNPs are population specific, it makes sense that an individual homozygous for all “good” alleles should be admixed. And that is exactly what Puerto Ricans are. In a “women in the diaspora” study, Puerto Rican women born on the island but living in the United States were shown to be 53.3±2.8% European, 29.1±2.3% West African, and 17.6±2.4% Native American. In other words, to collect all the “good” alleles it is necessary to be admixed, but admixture itself is not sufficient for perfection. On a personal note, I was happy to see population genetic evidence supporting my admiration for the perennial championship Puerto Rico All Stars team:

As for Watson, it seems fitting that he should donate the proceeds of his auction to the Caribbean Genome Center at the University of Puerto Rico.

[Update: Dec. 7/8: Taras Oleksyk from the Department of Biology at the University of Puerto Rico Mayaguez has written an excellent post-publication peer review of this blog post and Rafael Irizarry from the Harvard School of Public Health has written a similar piece, Genéticamente, no hay tal cosa como la raza puertorriqueña in Spanish. Both are essential reading.]

In the Jeopardy! game show contestants are presented with questions formulated as answers that require answers in the form questions. For example, if a contestant selects “Normality for $200” she might be shown the following clue:

“The average ,”

to which she would reply “What is the maximum likelihood estimate for the mean of n independent identically distributed Gaussian random variables from which samples have been obtained?” Host Alex Trebek would immediately exclaim “That is the correct answer for $200!”

The process of doing mathematics involves repeatedly playing Jeopardy! with oneself in an unending quest to understand everything just a little bit better. The purpose of this blog post is to provide an exposition of how this works for understanding principal component analysis (PCA): I present four Jeopardy clues in the “Normality” category that all share the same answer: “What is principal component analysis?” The post was motivated by a conversation I recently had with a well-known population geneticist at a conference I was attending. I mentioned to him that I would be saying something about PCA in my talk, and that he might find what I have to say interesting because I knew he had used the method in many of his papers. Without hesitation he replied that he was well aware that PCA was not a statistical method and merely a heuristic visualization tool.

The problem, of course, is that PCA does have a statistical interpretation and is not at all an ad-hoc heuristic. Unfortunately, the previously mentioned population geneticist is not alone; there is a lot of confusion about what PCA is really about. For example, in one textbook it is stated that “PCA is not a statistical method to infer parameters or test hypotheses. Instead, it provides a method to reduce a complex dataset to lower dimension to reveal sometimes hidden, simplified structure that often underlie it.” In another one finds out that “PCA is a statistical method routinely used to analyze interrelationships among large numbers of objects.” In a highly cited review on gene expression analysis PCA is described as “more useful as a visualization technique than as an analytical method” but then in a paper by Markus Ringnér titled the same as this post, i.e. What is principal component analysis? in Nature Biotechnology, 2008, the author writes that “Principal component analysis (PCA) is a mathematical algorithm that reduces the dimensionality of the data while retaining most of the variation in the data set” (the author then avoids going into the details because “understanding the details underlying PCA requires knowledge of linear algebra”). All of these statements are both correct and incorrect and confusing. A major issue is that the description by Ringnér of PCA in terms of the procedure for computing it (singular value decomposition) is common and unfortunately does not shed light on when it should be used. But knowing when to use a method is far more important than knowing how to do it.

I therefore offer four Jeopardy! clues for principal component analysis that I think help to understand both when and how to use the method:

1. An affine subspace closest to a set of points.

Suppose we are given n numbers as in the initial example above. We are interested in finding the “closest” number to these numbers. By “closest” we mean in the sense of total squared difference. That is, we are looking for a number

such that

is minimized.

This is a (straightforward) calculus problem, solved by taking the derivative of the function above and setting it equal to zero. If we let then

and setting

we can solve for

to obtain

.

The right hand side of the equation is just the average of the n numbers and the optimization problem provides an interpretation of it as the number minimizing the total squared difference with the given numbers (note that one can replace squared difference by absolute value, i.e. minimization of , in which case the solution for m is the median; we return to this point and its implications for PCA later).

Suppose that instead of n numbers, one is given n points in . That is, point i is

. We can now ask for a point

with the property that the squared distance of

to the n points is minimized. This is asking for

.

The solution for can be obtained by minimizing each coordinate independently, thereby reducing the problem to the simpler version of numbers above, and it follows that

.

This is 0-dimensional PCA, i.e., PCA of a set of points onto a single point, and it is the centroid of the points. The generalization of this concept provides a definition for PCA:

Definition: Given n points in , principal components analysis consists of choosing a dimension

and then finding the affine space of dimension k with the property that the squared distance of the points to their orthogonal projection onto the space is minimized.

This definition can be thought of as a generalization of the centroid (or average) of the points. To understand this generalization, it is useful to think of the simplest case that is not 0-dimensional PCA, namely 1-dimensional PCA of a set of points in two dimensions:

In this case the 1-dimensional PCA subspace can be thought of as the line that best represents the average of the points. The blue points are the orthogonal projections of the points onto the “average line” (see, e.g., the red point projected orthogonally), which minimizes the squared lengths of the dashed lines. In higher dimensions line is replaced by affine subspace, and the orthogonal projections are to points on that subspace. There are a few properties of the PCA affine subspaces that are worth noting:

In this case the 1-dimensional PCA subspace can be thought of as the line that best represents the average of the points. The blue points are the orthogonal projections of the points onto the “average line” (see, e.g., the red point projected orthogonally), which minimizes the squared lengths of the dashed lines. In higher dimensions line is replaced by affine subspace, and the orthogonal projections are to points on that subspace. There are a few properties of the PCA affine subspaces that are worth noting:

- The set of PCA subspaces (translated to the origin) form a flag. This means that the PCA subspace of dimension k is contained in the PCA subspace of dimension k+1. For example, all PCA subspaces contain the centroid of the points (in the figure above the centroid is the green point). This follows from the fact that the PCA subspaces can be incrementally constructed by building a basis from eigenvectors of a single matrix, a point we will return to later.

- The PCA subspaces are not scale invariant. For example, if the points are scaled by multiplying one of the coordinates by a constant, then the PCA subspaces change. This is obvious because the centroid of the points will change. For this reason, when PCA is applied to data obtained from heterogeneous measurements, the units matter. One can form a “common” set of units by scaling the values in each coordinate to have the same variance.

- If the data points are represented in matrix form as an

matrix

, and the points orthogonally projected onto the PCA subspace of dimension k are represented as in the ambient p dimensional space by a matrix

, then

. That is,

is the matrix of rank k with the property that the Frobenius norm

is minimized. This is just a rephrasing in linear algebra of the definition of PCA given above.

At this point it is useful to mention some terminology confusion associated with PCA. Unfortunately there is no standard for describing the various parts of an analysis. What I have called the “PCA subspaces” are also sometimes called “principal axes”. The orthogonal vectors forming the flag mentioned above are called “weight vectors”, or “loadings”. Sometimes they are called “principal components”, although that term is sometimes used to refer to points projected onto a principal axis. In this post I stick to “PCA subspaces” and “PCA points” to avoid confusion.

Returning to Jeopardy!, we have “Normality for $400” with the answer “An affine subspace closest to a set of points” and the question “What is PCA?”. One question at this point is why the Jeopardy! question just asked is in the category “Normality”. After all, the normal distribution does not seem to be related to the optimization problem just discussed. The connection is as follows:

2. A generalization of linear regression in which the Gaussian noise is isotropic.

PCA has an interpretation as the maximum likelihood parameter of a linear Gaussian model, a point that is crucial in understanding the scope of its application. To explain this point of view, we begin by elaborating on the opening Jeopardy! question about Normality for $200:

The point of the question was that the average of n numbers can be interpreted as a maximum likelihood estimation of the mean of a Gaussian. The Gaussian distribution is

. Given the numbers

, the likelihood function is therefore

. The maximum of this function is the same as the maximum of its logarithm, which is

. Therefore the problem of finding the maximum likelihood estimate for the mean is equivalent to that of finding the minimum of the function

. This is exactly the optimization problem solved by 0-dimensional PCA, as we saw above. With this calculation at hand, we turn to the statistical interpretation of least squares:

Given n points in the plane (see figure above), the least squares line

(purple in figure) is the one that minimizes the sum of the squares

. That is, the least squares line is the one minimizing the sum of the squared vertical distances to the points. As with the average of numbers, the least squares line has a statistical interpretation: Suppose that there is some line

(black line in figure) that is unknown, but that “generated” the observed points, in the sense that each observed point i was obtained by perturbing the point

vertically by a random amount from a single Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and variance

. In the figure, an example is shown where the blue point on the unknown line “generates” the observed red point; the Gaussian is indicated with the blue streak around the point. Note that the model specified so far is not fully generative, as it depends on the hidden points

and there is no procedure given to generate the

. This can be done by positing that the

are generated from a Gaussian distribution along the line

(followed by the points

generated by Gaussian perturbation of the y coordinate on the line). The coordinates

can then be deduced directly from the observed points as the Gaussian perturbations are all vertical. The relationship between the statistical model just described and least squares is made precise by a theorem (which we state informally, but is a special case of the Gauss-Markov theorem):

Theorem (Gauss-Markov): The maximum likelihood estimate for the line (the parameters m and b) in the model described above correspond to the least squares line.

The proof is analogous to the argument given for the average of numbers above so we omit it. It can be generalized to higher dimensions where it forms the basis of what is known as linear regression. In regression, the are known as independent variables and

the dependent variable. The generative model provides an interpretation of the independent variables as fixed measured quantities, whereas the dependent variable is a linear combination of the independent variables with added noise. It is important to note that the origins of linear regression are in physics, specifically in work of Legendre (1805) and Gauss (1809) who applied least squares to the astronomical problem of calculating the orbits of comets around the sun. In their application, the independent variables were time (for which accurate measurements were possible with clocks; by 1800 clocks were accurate to less than 0.15 seconds per day) and the (noisy) dependent variable the measurement of location. Linear regression has become one of the most (if not the most) widely used statistical tools but as we now explain, PCA (and its generalization factor analysis), with a statistical interpretation that includes noise in the

variables, seems better suited for biological data.

The statistical interpretation of least squares can be extended to a similar framework for PCA. Recall that we first considered a statistical interpretation for least squares where an unknown line “generated” the observed points, in the sense that each observed point i was obtained by perturbing the point

vertically by a random amount from a single Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and variance

. PCA can be understood analogously by replacing vertically by orthogonally (this is the probabilistic model of Collins et al., NIPS 2001 for PCA). However this approach is not completely satisfactory as the orthogonality of the perturbation is is not readily interpretable. Stated differently, it is not obvious what physical processes would generate points orthogonal to a linear affine subspace by perturbations that are always orthogonal to the subspace. In the case of least squares, the “vertical” perturbation corresponds to noise in one measurement (represented by one coordinate). The problem is in naturally interpreting orthogonal perturbations in terms of a noise model for measurements. This difficulty is resolved by a model called probabilistic PCA (pPCA), first proposed by Tipping and Bishop in a Tech Report in 1997, and published in the J. of the Royal Statistical Society B 2002, and independently by Sam Roweis, NIPS 1998, that is illustrated visually in the figure below, and that we now explain:

In the pPCA model there is an (unknown) line (affine space in higher dimension) on which (hidden) points (blue) are generated at random according to a Gaussian distribution (represented by gray streak in the figure above, where the mean of the Gaussian is the green point). Observed points (red) are then generated from the hidden points by addition of isotropic Gaussian noise (blue smear), meaning that the Gaussian has a diagonal covariance matrix with equal entries. Formally, in the notation of Tipping and Bishop, this is a linear Gaussian model described as follows:

Observed random variables t are given by where x are latent (hidden) random variables, W is a matrix describing a subspace and

are the latent points on an affine subspace (

corresponds to a translation). Finally,

is an error term, given by a Gaussian random variable with mean 0 and covariance matrix

. The parameters of the model are

and

. Equivalently, the observed random variables are themselves Gaussian, described by the distribution

where

. Tipping and Bishop prove an analogy of the Gauss-Markov theorem, namely that the affine subspace given by the maximum likelihood estimates of

and

is the PCA subspace (the proof is not difficult but I omit it and refer interested readers to their paper, or Bishop’s Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning book).

It is important to note that although the maximum likelihood estimates of in the pPCA model correspond to the PCA subspace, only posterior distributions can be obtained for the latent data (points on the subspace). Neither the mode nor the mean of those distributions corresponds to the PCA points (orthogonal projections of the observations onto the subspace). However what is true, is that the posterior distributions converge to the PCA points as

. In other words, the relationship between pPCA and PCA is a bit more subtle than that between least squares and regression.

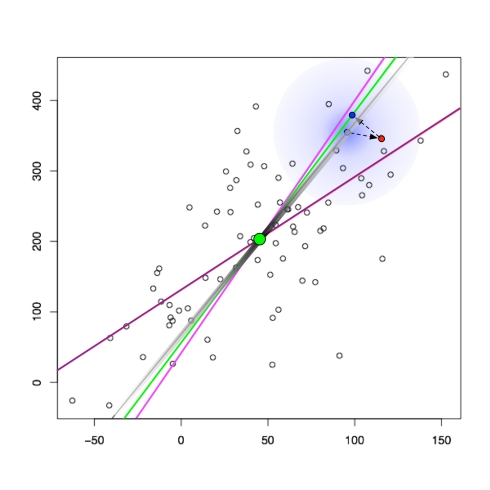

The relationship between regression and (p)PCA is shown in the figure below:

In the figure, points have been generated randomly according to the pPCA model. the black smear shows the affine space on which the points were generated, with the smear indicating the Gaussian distribution used. Subsequently the latent points (light blue on the gray line) were used to make observed points (red) by the addition of isotropic Gaussian noise. The green line is the maximum likelihood estimate for the space, or equivalently by the theorem of Tipping and Bishop the PCA subspace. The projection of the observed points onto the PCA subspace (blue) are the PCA points. The purple line is the least squares line, or equivalently the affine space obtained by regression (y observed as a noisy function of x). The pink line is also a regression line, except where x is observed as a noisy function of y.

In the figure, points have been generated randomly according to the pPCA model. the black smear shows the affine space on which the points were generated, with the smear indicating the Gaussian distribution used. Subsequently the latent points (light blue on the gray line) were used to make observed points (red) by the addition of isotropic Gaussian noise. The green line is the maximum likelihood estimate for the space, or equivalently by the theorem of Tipping and Bishop the PCA subspace. The projection of the observed points onto the PCA subspace (blue) are the PCA points. The purple line is the least squares line, or equivalently the affine space obtained by regression (y observed as a noisy function of x). The pink line is also a regression line, except where x is observed as a noisy function of y.

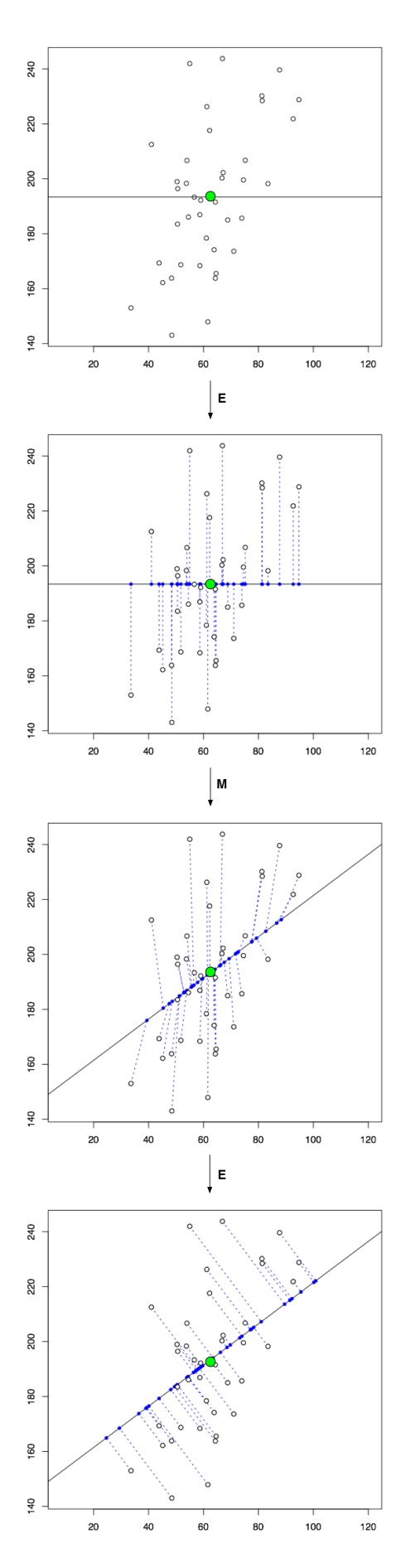

A natural question to ask is why the probabilistic interpretation of PCA (pPCA) is useful or necessary? One reason it is beneficial is that maximum likelihood inference for pPCA involves hidden random variables, and therefore the EM algorithm immediately comes to mind as a solution (the strategy was suggested by both Tipping & Bishop and Roweis). I have not yet discussed how to find the PCA subspace, and the EM algorithm provides an intuitive and direct way to see how it can be done, without the need for writing down any linear algebra:

The exact version of the EM shown above is due to Roweis. In it, one begins with a random affine subspace passing through the centroid of the points. The “E” step (expectation) consists of projecting the points to the subspace. The projected points are considered fixed to the subspace. The “M” step (maximization) then consists of rotating the space so that the total squared distance of the fixed points on the subspace to the observed points is minimized. This is repeated until convergence. Roweis points out that this approach to finding the PCA subspace is equivalent to power iteration for (efficiently) finding eigenvalues of the the sample covariance matrix without computing it directly. This is our first use of the word eigenvalue in describing PCA, and we elaborate on it, and the linear algebra of computing PCA subspaces later in the post.

Another point of note is that pPCA can be viewed as a special case of factor analysis, and this connection provides an immediate starting point for thinking about generalizations of PCA. Specifically, factor analysis corresponds to the model where the covariance matrix

is less constrained, and only required to be diagonal. This is connected to a comment made above about when the PCA subspace might be more useful as a linear fit to data than regression. To reiterate, unlike physics, where some coordinate measurements have very little noise in comparison to others, biological measurements are frequently noisy in all coordinates. In such settings factor analysis is preferable, as the variance in each coordinate is estimated as part of the model. PCA is perhaps a good compromise, as PCA subspaces are easier to find than parameters for factor analysis, yet PCA, via its pPCA interpretation, accounts for noise in all coordinates.

A final comment about pPCA is that it provides a natural framework for thinking about hypothesis testing. The book Statistical Methods: A Geometric Approach by Saville and Wood is essentially about (the geometry of) pPCA and its connection to hypothesis testing. The authors do not use the term pPCA but their starting point is exactly the linear Gaussian model of Tipping and Bishop. The idea is to consider single samples from n independent identically distributed independent Gaussian random variables as one single sample from a high-dimensional multivariate linear Gaussian model with isotropic noise. From that point of view pPCA provides an interpretation for Bessel’s correction. The details are interesting but tangential to our focus on PCA.

We are therefore ready to return to Jeopardy!, where we have “Normality for $600” with the answer “A generalization of linear regression in which the Gaussian noise is isotropic” and the question “What is PCA?”

3. An orthogonal projection of points onto an affine space that maximizes the retained sample variance.

In the previous two interpretations of PCA, the focus was on the PCA affine subspace. However in many uses of PCA the output of interest is the projection of the given points onto the PCA affine space. The projected points have three useful related interpretations:

- As seen in in section 1, the (orthogonally) projected points (red -> blue) are those whose total squared distance to the observed points is minimized.

- What we focus on in this section, is the interpretation that the PCA subspace is the one onto which the (orthogonally) projected points maximize the retained sample variance.

- The topic of the next section, namely that the squared distances between the (orthogonally) projected points are on average (in the

metric) closest to the original distances between the points.

The sample variance of a set of points is the average squared distance from each point to the centroid. Mathematically, if the observed points are translated so that their centroid is at zero (known as zero-centering), and then represented by an matrix X, then the sample covariance matrix is given by

and the sample variance is given by the trace of the matrix. The point is that the jth diagonal entry of

is just

, which is the sample variance of the jth variable. The PCA subspace can be viewed as that subspace with the property that the sample variance of the projections of the observed points onto the subspace is maximized. This is easy to see from the figure above. For each point (blue), Pythagoras’ theorem implies that

. Since the PCA subspace is the one minimizing the total squared red-blue distances, and since the solid black lines (red-green distances) are fixed, it follows that the PCA subspace also maximizes the total squared green-blue distances. In other words, PCA maximizes the retained sample variance.

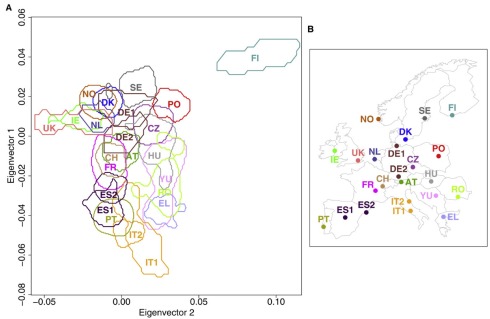

The explanation above is informal, and uses a 1-dimensional PCA subspace in dimension 2 to make the argument. However the argument extends easily to higher dimension, which is typically the setting where PCA is used. In fact, PCA is typically used to “visualize” high dimensional points by projection into dimensions two or three, precisely because of the interpretation provided above, namely that it retains the sample variance. I put visualize in quotes because intuition in two or three dimensions does not always hold in high dimensions. However PCA can be useful for visualization, and one of my favorite examples is the evidence for genes mirroring geography in humans. This was first alluded to by Cavalli-Sforza, but definitively shown by Lao et al., 2008, who analyzed 2541 individuals and showed that PCA of the SNP matrix (approximately) recapitulates geography:

Genes mirror geography from Lao et al. 2008: (Left) PCA of the SNP matrix (2541 individuals x 309,790 SNPs) showing a density map of projected points. (Right) Map of Europe showing locations of the populations .

In the picture above, it is useful to keep in mind that the emergence of geography is occurring in that projection in which the sample variance is maximized. As far as interpretation goes, it is useful to look back at Cavalli-Sforza’s work. He and collaborators who worked on the problem in the 1970s, were unable to obtain a dense SNP matrix due to limited technology of the time. Instead, in Menozzi et al., 1978 they performed PCA of an allele-frequency matrix, i.e. a matrix indexed by populations and allele frequencies instead of individuals and genotypes. Unfortunately they fell into the trap of misinterpreting the biological meaning of the eigenvectors in PCA. Specifically, they inferred migration patterns from contour plots in geographic space obtained by plotting the relative contributions from the eigenvectors, but the effects they observed turned out to be an artifact of PCA. However as we discussed above, PCA can be used quantitatively via the stochastic process for which it solves maximum likelihood inference. It just has to be properly understood.

To conclude this section in Jeopardy! language, we have “Normality for $800” with the answer “A set of points in an affine space obtained via projection of a set of given points so that the sample variance of the projected points is maximized” and the question “What is PCA?”

4. Principal component analysis of Euclidean distance matrices.

In the preceding interpretations of PCA, I have focused on what happens to individual points when projected to a lower dimensional subspace, but it is also interesting to consider what happens to pairs of points. One thing that is clear is that if a pair of points are projected orthogonally onto a low-dimensional affine subspace then the distance between the points in the projection is smaller than the original distance between the points. This is clear because of Pythagoras’ theorem, which implies that the squared distance will shrink unless the points are parallel to the subspace in which case the distance remains the same. An interesting observation is that in fact the PCA subspace is the one with the property where the average (or total) squared distances between the points is maximized. To see this it again suffices to consider only projections onto one dimension (the general case follows by Pythagoras’ theorem). The following lemma, discussed in my previous blog post, makes the connection to the previous discussion:

Lemma: Let be numbers with mean

. If the average squared distance between pairs of points is denoted

and the variance is denoted

then

.

What the lemma says is that the sample variance is equal to the average squared difference between the numbers (i.e. it is a scalar multiple that does not depend on the numbers). I have already discussed that the PCA subspace maximizes the retained variance, and it therefore follows that it also maximizes the average (or total) projected squared distance between the points. Alternately, PCA can be interpreted as minimizing the total (squared) distance that is lost, i,e. if the original distances between the points are given by a distance matrix and the projected distances are given by

, then the PCA subspace minimizes

, where each term in the sum is positive as discussed above.

This interpretation of PCA leads to an interesting application of the method to (Euclidean) distance matrices rather than points. The idea is based on a theorem of Isaac Schoenberg that characterizes Euclidean distance matrices and provides a method for realizing them. The theorem is well-known to structural biologists who work with NMR, because it is one of the foundations used to reconstruct coordinates of structures from distance measurements. It requires a bit of notation: D is a distance matrix with entries and

is the matrix with entries

.

denotes the vector of all ones, and

denotes a vector.

Theorem (Schoenberg, 1938): A matrix D is a Euclidean distance matrix if and only if the matrix is positive semi-definite where

.

For the case when is chosen to be a unit vector, i.e. all entries are zero except one of them equal to 1, the matrix B can be viewed as the Gromov transform (known as the Farris transform in phylogenetics) of the matrix with entries

. Since the matrix B is positive semidefinite it can be written as

, where the matrix X provides coordinates for points that realize D. At this point PCA can be applied resulting in a principal subspace and points on it (the orthogonal projections of X). A point of note is that eigenvectors of

can be computed directly, avoiding the need to compute

which may be a larger matrix if

.

The procedure just described is called classic multidimensional scaling (MDS) and it returns a set of points on a Euclidean subspace with distance matrix that best represent the original distance matrix D in the sense that

is minimized. The term multidimensional scaling without the “classic” has taken on an expanded meaning, namely it encapsulates all methods that seek to approximately realize a distance matrix by points in a low dimensional Euclidean space. Such methods are generally not related to PCA, but classic multidimensional scaling is PCA. This is a general source of confusion and error on the internet. In fact, most articles and course notes I found online describing the connection between MDS and PCA are incorrect. In any case classic multidimensional scaling is a very useful instance of PCA, because it extends the utility of the method to cases where points are not available but distances between them are.

Now we return to Jeopardy! one final time with the final question in the category: “Normality for $1000”. The answer is “Principal component analysis of Euclidean distance matrices” and the question is “What is classic multidimensional scaling?”

An example

To illustrate the interpretations of PCA I have highlighted, I’m including an example in R inspired by an example from another blog post (all commands can be directly pasted into an R console). I’m also providing the example because missing in the discussion above is a description of how to compute PCA subspaces and the projections of points onto them. I therefore explain some of this math in the course of working out the example:

First, I generate a set of points (in ). I’ve chosen a low dimension so that pictures can be drawn that are compatible with some of the examples above. Comments following commands appear after the # character.

set.seed(2) #sets the seed for random number generation. x <- 1:100 #creates a vector x with numbers from 1 to 100 ex <- rnorm(100, 0, 30) #100 normally distributed rand. nos. w/ mean=0, s.d.=30 ey <- rnorm(100, 0, 30) # " " y <- 30 + 2 * x #sets y to be a vector that is a linear function of x x_obs <- x + ex #adds "noise" to x y_obs <- y + ey #adds "noise" to y P <- cbind(x_obs,y_obs) #places points in matrix plot(P,asp=1,col=1) #plot points points(mean(x_obs),mean(y_obs),col=3, pch=19) #show center

At this point a full PCA analysis can be undertaken in R using the command “prcomp”, but in order to illustrate the algorithm I show all the steps below:

M <- cbind(x_obs-mean(x_obs),y_obs-mean(y_obs))#centered matrix MCov <- cov(M) #creates covariance matrix

Note that the covariance matrix is proportional to the matrix $M^tM$. Next I turn to computation of the principal axes:

eigenValues <- eigen(MCov)$values #compute eigenvalues eigenVectors <- eigen(MCov)$vectors #compute eigenvectors

The eigenvectors of the covariance matrix provide the principal axes, and the eigenvalues quantify the fraction of variance explained in each component. This math is explained in many papers and books so we omit it here, except to say that the fact that eigenvalues of the sample covariance matrix are the principal axes follows from recasting the PCA optimization problem as maximization of the Raleigh quotient. A key point is that although I’ve computed the sample covariance matrix explicitly in this example, it is not necessary to do so in practice in order to obtain its eigenvectors. In fact, it is inadvisable to do so. Instead, it is computationally more efficient, and also more stable to directly compute the singular value decomposition of M. The singular value decomposition of M decomposes it into where D is a diagonal matrix and both

and

are orthogonal matrices. I will also not explain in detail the linear algebra of singular value decomposition and its relationship to eigenvectors of the sample covariance matrix (there is plenty of material elsewhere), and only show how to compute it in R:

d <- svd(M)$d #the singular values v <- svd(M)$v #the right singular vectors

The right singular vectors are the eigenvectors of . Next I plot the principal axes:

lines(x_obs,eigenVectors[2,1]/eigenVectors[1,1]*M[x]+mean(y_obs),col=8)

This shows the first principal axis. Note that it passes through the mean as expected. The ratio of the eigenvectors gives the slope of the axis. Next

lines(x_obs,eigenVectors[2,2]/eigenVectors[1,2]*M[x]+mean(y_obs),col=8)

shows the second principal axis, which is orthogonal to the first (recall that the matrix in the singular value decomposition is orthogonal). This can be checked by noting that the second principal axis is also

lines(x_obs,-1/(eigenVectors[2,1]/eigenVectors[1,1])*M[x]+mean(y_obs),col=8)

as the product of orthogonal slopes is -1. Next, I plot the projections of the points onto the first principal component:

trans <- (M%*%v[,1])%*%v[,1] #compute projections of points P_proj <- scale(trans, center=-cbind(mean(x_obs),mean(y_obs)), scale=FALSE) points(P_proj, col=4,pch=19,cex=0.5) #plot projections segments(x_obs,y_obs,P_proj[,1],P_proj[,2],col=4,lty=2) #connect to points

The linear algebra of the projection is simply a rotation followed by a projection (and an extra step to recenter to the coordinates of the original points). Formally, the matrix M of points is rotated by the matrix of eigenvectors W to produce . This is the rotation that has all the optimality properties described above. The matrix T is sometimes called the PCA score matrix. All of the above code produces the following figure, which should be compared to those shown above:

There are many generalizations and modifications to PCA that go far beyond what has been presented here. The first step in generalizing probabilistic PCA is factor analysis, which includes estimation of variance parameters in each coordinate. Since it is rare that “noise” in data will be the same in each coordinate, factor analysis is almost always a better idea than PCA (although the numerical algorithms are more complicated). In other words, I just explained PCA in detail, now I’m saying don’t use it! There are other aspects that have been generalized and extended. For example the Gaussian assumption can be relaxed to other members of the exponential family, an important idea if the data is discrete (as in genetics). Yang et al. 2012 exploit this idea by replacing PCA with logistic PCA for analysis of genotypes. There are also many constrained and regularized versions of PCA, all improving on the basic algorithm to deal with numerous issues and difficulties. Perhaps more importantly, there are issues in using PCA that I have not discussed. A big one is how to choose the PCA dimension to project to in analysis of high-dimensional data. But I am stopping here as I am certain no one is reading at this far into the post anyway…

The take-home message about PCA? Always be thinking when using it!

Acknowledgment: The exposition of PCA in this post began with notes I compiled for my course MCB/Math 239: 14 Lessons in Computational Genomics taught in the Spring of 2013. I thank students in that class for their questions and feedback. None of the material presented in class was new, but the exposition was intended to clarify when PCA ought to be used, and how. I was inspired by the papers of Tipping, Bishop and Roweis on probabilistic PCA in the late 1990s that provided the needed statistical framework for its understanding. Following the class I taught, I benefited greatly from conversations with Nicolas Bray, Brielin Brown, Isaac Joseph and Shannon McCurdy who helped me to further frame PCA in the way presented in this post.

The Habsburg rulership of Spain ended with an inbreeding coefficient of F=0.254. The last king, Charles II (1661-1700), suffered an unenviable life. He was unable to chew. His tongue was so large he could not speak clearly, and he constantly drooled. Sadly, his mouth was the least of his problems. He suffered seizures, had intellectual disabilities, and was frequently vomiting. He was also impotent and infertile, which meant that even his death was a curse in that his lack of heirs led to a war.

None of these problems prevented him from being married (twice). His first wife, princess Henrietta of England, died at age 26 after becoming deeply depressed having being married to the man for a decade. Only a year later, he married another princess, 23 year old Maria Anna of Neuberg. To put it mildly, his wives did not end up living the charmed life of Disney princesses, nor were they presumably smitten by young Charles II who apparently aged prematurely and looked the part of his horrific homozygosity. The princesses married Charles II because they were forced to. Royals organized marriages to protect and expand their power, money and influence. Coupled to this were primogeniture rules which ensured that the sons of kings, their own flesh and blood and therefore presumably the best-suited to be in power, would indeed have the opportunity to succeed their fathers. The family tree of Charles II shows how this worked in Spain:

It is believed that the inbreeding in Charles II’s family led to two genetic disorders, combined pituitary hormone deficiency and distal renal tubular acidosis, that explained many of his physical and mental problems. In other words, genetic diversity is important, and the point of this blog post is to highlight the fact that diversity is important in education as well.

The problem of inbreeding in academia has been studied previously, albeit to a limited extent. One interesting article is Navel Grazing: Academic Inbreeding and Scientific Productivity by Horta et al published in 2010 (my own experience with an inbred academic from a department where 39% of the faculty are self-hires anecdotally confirms the claims made in the paper). But here I focus on the downsides of inbreeding of ideas rather than of faculty. For example home-schooling, the educational equivalent of primogeniture, can be fantastic if the parents happen to be good teachers, but can fail miserably if they are not. One thing that is guaranteed in a school or university setting is that learning happens by exposure to many teachers (different faculty, students, tutors, the internet, etc.) Students frequently complain when there is high variance in teaching quality, but one thing such variance ensures is that is is very unlikely that any student is exposed only to bad teachers. Diversity in teaching also helps to foster the development of new ideas. Different teachers, by virtue of insight or error, will occasionally “mutate” ideas or concepts for better or for worse. In other words, one does not have to fully embrace the theory of memes to acknowledge that there are benefits to variance in teaching styles, methods and pedagogy. Conversely, there is danger in homogeneity.

This brings me to MOOCs. One of the great things about MOOCs is that they reach millions of people. Udacity claims it has 1.6 million “users” (students?). Coursera claims 7.1 million. These companies are greatly expanding the accessibility of education. Starving children in India can now take courses in mathematical methods for quantitative finance, and for the first time in history, a president of the United States can discreetly take a freshman course on economics together with its high school algebra prerequisites (highly recommended). But when I am asked whether I would be interested in offering a MOOC I hesitate, paralyzed at the thought that any error I make would immediately be embedded in the brains of millions of innocent victims. My concern is this: MOOCs can greatly reduce the variance in education. For example, Coursera currently offers 641 courses, which means that each courses is or has been taught to over 11,000 students. Many college courses may have less than a few dozen students, and even large college courses rarely have more than a few hundred students. This means that on average, through MOOCs, individual professors reach many more (2 orders of magnitude!) students. A great lecture can end up positively impacting a large number of individuals, but at the same time, a MOOC can be a vehicle for infecting the brains of millions of people with nonsense. If that nonsense is then propagated and reaffirmed via the interactions of the people who have learned it from the same source, then the inbreeding of ideas has occurred.

I mention MOOCs because I was recently thinking about intuition behind Bessel’s correction replacing n with n-1 in the formula for sample variance. Formally, Bessel’s correction replaces the biased formula

for estimating the variance of a random variable from samples with

.

The switch from n to n-1 is a bit mysterious and surprising, and in introductory statistics classes it is frequently just presented as a “fact”. When an explanation is provided, it is usually in the form of algebraic manipulation that establishes the result. The issue came up as a result of a blog post I’m writing about principal components analysis (PCA), and I thought I would check for an intuitive explanation online. I googled “intuition sample variance” and the top link was a MOOC from the Khan Academy:

The video has over 51,000 views with over 100 “likes” and only 6 “dislikes”. Unfortunately, in this case, popularity is not a good proxy for quality. Despite the title promising “review” and “intuition” for “why we divide by n-1 for the unbiased sample variance” there is no specific reason given why n is replaced by n-1 (as opposed to another correction). Furthermore, the intuition provided has to do with the fact that underestimates

(where

is the mean of the random variable and

is the sample mean) but the explanation is confusing and not quantitative (which it can easily be). In fact, the wikipedia page for Bessel’s correction provides three different mathematical explanations for the correction together with the intuition that motivates them, but it is difficult to find with Google unless one knows that the correction is called “Bessel’s correction”.

Wikipedia is also not perfect, and this example is a good one for why teaching by humans is important. Among the three alternative derivations, I think that one stands out as “better” but one would not know by just looking at the wikipedia page. Specifically, I refer to “Alternate 1” on the wikipedia page, that is essentially explaining that variance can be rewritten as a double sum corresponding to the average squared distance between points and the diagonal terms of the sum are zero in expectation. An explanation of why this fact leads to the n-1 in the unbiased estimator is as follows:

The first step is to notice that the variance of a random variable is equal to half of the expected squared difference of two independent identically distributed random variables of that type. Specifically, the definition of variance is:

where

. Equivalently,

. Now suppose that Y is another random variable identically distributed to X and with X,Y independent. Then

. This is easy to see by using the fact that

.

This identity motivates a rewriting of the (uncorrected) sample variance in a way that is computationally less efficient, but mathematically more insightful:

.

Of note is that in this summation exactly n of the terms are zero, namely the terms when i=j. These terms are zero independently of the original distribution, and remain so in expectation thereby biasing the estimate of the variance, specifically leading to an underestimate. Removing them fixes the estimate and produces

.

It is easy to see that this is indeed Bessel’s correction. In other words, the correction boils down to the fact that , hence the appearance of n-1.

Why do I like this particular derivation of Bessel’s correction? There are two reasons: first, n-1 emerges naturally and obviously from the derivation. The denominator in matches exactly the number of terms being summed, so that it can be understood as a true average (this is not apparent in its standard form as

. There is really nothing mysterious anymore, its just that some terms having been omitted from the sum because they were non-inofrmative. Second, as I will show in my forthcoming blog post on PCA, the fact that the variance of a random variable is half of the expectation of the squared difference of two instances, is key to understanding the connection between multi-dimensional scaling (MDS) and PCA. In other words, as my student Nicolas Bray is fond of saying, although most people think a proof is either right or wrong, in fact some proofs are more right than others. The connection between Bessel’s correction and PCA goes even deeper: as explained by Saville and Wood in their book Statistical Methods: A Geometric Approach n-1 can be understood to be a reduction in one dimension from the point of view of probabilistic PCA (Saville and Wood do not explicitly use the term probabilistic PCA but as I will explain in my PCA post it is implicit in their book). Finally, there are many subtleties to Bessel’s correction, for example it is an unbiased estimator for variance and not standard deviation. These issues ought to be mentioned in a good lecture about the topic. In other words, the Khan lecture is neither necessary nor sufficient, but unlike a standard lecture where the damage is limited to a small audience of students, it has been viewed more than 50,000 times and those views cannot be unviewed.

In writing this blog post I pondered the irony of my call for added diversity in teaching while I preach my own idea (this post) to a large number of readers via a medium designed for maximal outreach. I can only ask that others blog as well to offer alternative points of view 🙂 and that readers inform themselves on the issues I raise by fact-checking elsewhere. As far as the statistics goes, if someone finds the post confusing, they should go and register for one of the many fantastic MOOCs on statistics! But I reiterate that in the rush to MOOCdom, providers must offer diversity in their offerings (even multiple lectures on the same topic) to ensure a healthy population of memes. This is especially true in Spain, where already inbred faculty are now inbreeding what they teach by MOOCing via Miriada X. Half of the MOOCs being offered in Spain originate from just 3 universities, while the number of potential viewers is enormous as Spanish is now the second most spoken language in the world (thanks to Charles II’s great-great-grandfather, Charles I).

May Charles II rest in peace.

Last Monday some biostatisticians/epidemiologists from Australia published a paper about a “visualization tool which may allow greater understanding of medical and epidemiological data”:

H. Wand et al., “Quilt Plots: A Simple Tool for the Visualisation of Large Epidemiological Data“, PLoS ONE 9(1): e85047.

A brief look at the “paper” reveals that the quilt plot they propose is a special case of what is commonly known as a heat map, a point the authors acknowledge, with the caveat that they claim that

” ‘heat maps’ require the specification of 21 arguments including hierarchical clustering, weights for reordering the row and columns dendrogram, which are not always easily understood unless one has an extensive programming knowledge and skills. One of the aims of our paper is to present ‘‘quilt plots’’ as a useful tool with simply formulated R-functions that can be easily understood by researchers from different scientific backgrounds without high-level programming skills.”

In other words, the quilt plot is a simplified heat map and the authors think it should be used because specifying parameters for a heat map (in R) would require a terrifying skill known as programming. This is of course all completely ridiculous. Not only does usage of R not require programming skill, there are also simplified heat map functions in many programming languages/computation environments that are as simple as the quilt plot function.

The fact that a paper like this was published in a journal is preposterous, and indeed the authors and editor of the paper have been ridiculed on social media, blogs and in comments to their paper on the PLoS One website.

BUT…

Wand et al. do have one point… those 21 parameters are not an entirely trivial matter. In fact, the majority of computational biologists (including many who have been ridiculing Wand) appear not to understand heat maps themselves, despite repeatedly (ab)using them in their own work.

What are heat maps?

In the simplest case, heat maps are just the conversion of a table of numbers into a grid with colored squares, where the colors represent the magnitude of the numbers. In the quilt plot paper that is the type of heat map considered. However in applications such as gene expression analysis, heat maps are used to visualize distances between experiments.

Heat maps have been popular for visualizing multiple gene expression datasets since the publication of the “Eisengram” (or the guilt plot?). So when my student Lorian Schaeffer and I recently needed to create a heat map from RNA-Seq abundance estimates in multiple samples we are analyzing with Ryan Forster and Dirk Hockemeyer, we assumed there would be a standard method (and software) we could use. However when starting to look at the literature we quickly found 3 papers with 4 different opinions about which similarity measure to use:

- In “The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs“, Brawand et al., Nature 478 (2011), 343-348, the authors use two different distance measures for evaluating the similarity between samples. They use the measure

where

is Spearman’s rank correlation (Supplementary figure S2) and also the Euclidean distance (Supplementary figure S3).

- In “Differential expression analysis for sequence count data“, Anders and Huber, Genome Biology 11 (2010), R106, a heat map tool is provided that is based on Euclidean distance but differs from the method in Brawand et al. by first performing variance stabilization on the abundance estimates.

- In “Evolutionary Dynamics of Gene and Isoform Regulation in Mammalian Tissues“, Merkin et al., Science 338 (2012), a heat map is displayed based on the Jensen-Shannon metric.

There are also the folks who don’t worry too much and just try anything and everything (for example using the heatmap.2 function in R) hoping that some distance measure produces the figure they need for their paper. There are certainly a plethora of distance measures for them to try out. And even if none of the distance measures provide the needed figure, there is always the opportunity to play with the colors and shading to “highlight” the desired result. In other words, heat maps are great for cheating with what appears to be statistics.

We wondered… what is the “right” way to make a heat map?

Consider first the obvious choice for measuring similarity: Euclidean distance. Suppose that we are estimating the distance between abundance estimates from two RNA-Seq experiments, where for simplicity we assume that there are only three transcripts (A,B,C). The two abundance estimates can be represented by 3-tuples and

such that both

and

. If

and

, then the Euclidean distance is given by

. This obviously depends on

and

, a dependence that is problematic. What has changed between the two RNA-Seq experiments is that transcript

has gone from being the only one transcribed, to not being transcribed at all. It is difficult to justify a distance metric that depends on the relative changes in

and

. Why, for example, should

be closer to

than to

?

The Jensen-Shannon divergence, defined for two distributions and

by

where and

is the Kullback-Leibler divergence, is an example of a distance measure that does not have this problem. For the example above the JSD is always

(regardless of

and

). However the JSD is not a metric (hence the term divergence in its name). In particular, it does not satisfy the triangle inequality (which the Euclidean distance does). Interestingly, this defect can be rectified by replacing JSD with the square root of JSD (the JSD metric). Formal proofs that the square root of JSD is a metric were provided in “A new Metric for Probability Distributions” by Dominik Endres and Johannes Schindelin (2003), and separately (and independently) in “A new class of metric divergences on probability spaces and its applicability in statistics” by Ferdinand Österreicher and Igor Vajda (2003). The paper “Jensen-Shannon Divergence and Hilbert space embedding” by Bent Fuglede and Flemming Topsøe (2004) makes clear the mathematical origins for this result by showing that the square root of JSD can be isometrically embedded into Hilbert space (as a logarithmic spiral)

The 2-simplex with contour lines showing points equidistant

from the probability distribution (1/3, 1/3, 1/3) for the JSD metric.

The meaning of the JSD metric is not immediately apparent based on its definition, but a number of results provide some insight. First, the JSD metric can be approximated by Pearson’s distance (Equation (7) in Endres and Schindelin). This relationship is confirmed in the numerical experiments of Sung-Hyuk Cha (see Figure 3 in “Comprehensive survey on distance/similarity measures between probability distance functions“, in particular the close relationship between JSD and the probabilistic symmetric

). There are also information theoretic and physical interpretations for the JSD metric stemming from the definition of JSD in terms of Kullback-Leibler divergence.

In “Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation“, Trapnell et al., Nature Biotechnology 28 (2010), we used the JSD metric to examine changes to relative isoform abundances in genes (see, for example, the Minard plot in Figure 2c). This application of the JSD metric makes sense, however the JSD metric is not a panacea. Consider Figure 1 in the Merkin et al. paper mentioned above. It displays a heat map generated from 7713 genes (genes with singleton orthologs in the five species studied). Some of these genes will have higher expression, and therefore higher variance, than others. The nature of the JSD metric is such that those genes will dominate the distance function, so that the heat map is effectively generated only from the highly abundant genes. Since there is typically an (approximately) exponential distribution of transcript abundance this means that, in effect, very few genes dominate the analysis.

I started thinking about this issue with my student Nicolas Bray and we began by looking at the first obvious candidate for addressing the issue of domination by high variance genes: the Mahalanobis distance. Mahalanobis distance is an option in many heat map packages (e.g. in R), but has been used only rarely in publications (although there is some history of its use in the analyses of microarray data). Intuitively, Mahalanobis distance seeks to remedy the problem of genes with high variance among the samples dominating the distance calculation by appropriate normalization. This appears to have been the aim of the method in the Anders and Huber paper cited above, where the expression values are first normalized to obtain equal variance for each gene (the variance stabilization procedure). Mahalanobis distance goes a step further and better, by normalizing using the entire covariance matrix (as opposed to just its diagonal).

Intuitively, given a set of points in some dimension, the Mahalanobis distance is the Euclidean distance between the points after they have been transformed via a linear transformation that maps an ellipsoid fitted to the points to a sphere. Formally, I think it is best understood in the following slightly more general terms:

Given an expression matrix

(rows=transcripts, columns=experiments), let

be the matrix consisting of projections of

onto its principal components, and denote by

the distance between projection of points i and j onto the kth component, i.e.

. Let

be the singular values. For some

, define the distance

When and

then the distance D defined above is the Mahalanobis distance.

The Mahalanobis ellipses. In this figure the distance shown is from every point to the center (mean of the point) rather than between pairs of points. Mahalanobis distance is sometimes defined in this way. The figure is reproduced from this website. Note that the Anders-Huber heat map produces distances looking only at the variance in each direction (in this case horizontal and vertical) which assumes that the gene expression values are independent, or equivalently that the ellipse is not rotated.

It is interesting to note that D is defined even when , providing a generalization of Mahalanobis distance for high-dimensional data.

The cutoff p involves ignoring the last few principal components. The reason one might want to do this is that the last few principal components presumably correspond to noise in the data. Amplifying this noise and treating it the same as the signal is not desirable. This is because as p increases the denominators get smaller, and therefore have an increasing effect on the distance. So even though it makes sense to normalize by variance thereby allowing all genes to count the same, it is important to keep in mind that the last few principal components may be desirable to toss out. One way one could choose the appropriate threshold is by examination of a scree plot.

We’re still not completely happy with Mahalanobis distance. For example, unlike the Jensen-Shannon metric, it does not provide a metric over probability distributions. In functional genomics, almost all *Seq assays produce an output which is a (discrete) probability distribution (for example in RNA-Seq the output after quantification is a probability distribution on the set of transcripts). So making heat maps for such data seems to not be entirely trivial…

Does any of this matter?

The landmark Michael Eisen et al. paper “Cluster analysis and the display of genome-wide expression patterns“, PNAS 95 (1998), 14863–14868 describing the “Eisengram” was based on correlation as the distance measure between expression vectors. This has a similar problem to the issues we discussed above, namely that abundant genes are weighted more heavily in the distance measure, and therefore they define the characteristics of the heat map. Yet the Eisengram and its variants have proven to be extremely popular and useful. It is fair to ask whether any of the issues I’ve raised matter in practice.

Depends. In many papers the heat map is a visualization tool intended for a qualitative exploration of the data. The issues discussed here touch on quantitative aspects, and in some applications changing distance measures may not change the qualitative results. Its difficult to say without reanalyzing data sets and (re)creating the heat maps with different parameters. Regardless, as expression technology continues to transition from microarrays to RNA-Seq, the demand for quantitative results is increasing. So I think it does matters how heat maps are made. Of course its easy to ridicule Handan Wand for her quilt plots, but I think those guilty of pasting ad-hoc heat maps based on arbitrary distance measures in their papers are really the ones that deserve a public spanking.

P.S. If you’re going to make your own heat map, after adhering to sound statistics, please use a colorblind-friendly palette.

P.P.S. In this post I have ignored the issue of clustering, namely how to order the rows and columns of heat maps so that similar expression profiles cluster together. This goes along with the problem of constructing meaningful dendograms, a visualization that has been a major factor in the popularization of the Eisengram. The choice of clustering algorithm is just as important as the choice of similarity measure, but I leave this for a future post.

Recent Comments