The All of Us Research Program, whose mission is to “to accelerate health research and medical breakthroughs, enabling individualized prevention, treatment, and care for all of us”, recently published a flagship paper in Nature on “Genomic Data in the All of Us Research Program“. This is a review of Figure 2 from the paper (referred to below as AoURFig2).

Background

The first U.S. Census that commenced on August 2, 1790 included a record of the race of individuals. It used three categories: “free whites”, “all other free persons”, and “slaves”. Since that time, racial categories as defined for the U.S. Census have been a recurring controversial topic, with categories changing many times over the years. The category “Mulatto”, which was introduced in 1850, shockingly remained in place until 1930. Mulatto, which comes from the Spanish word for mule (the hybrid offspring of a horse and a donkey), was used for multiracial individuals of African and European descent. In the most recent decennial census in 2020, the race categories used were determined by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and were “White”, “Black or African American”, “American Indian or Alaska Native”, “Asian”, “Native Hawaiian” or “Other Pacific Islander”, and a sixth category “Some Other Race” for people who do not identify with any of the aforementioned five races. Separately, the 2020 census included standards for ethnicity which were first introduced in 1977 as part of OMB Directive No. 15. Two ethnicity categories were introduced: “Hispanic or Latino” and “Not Hispanic or Latino”. The OMB was specific that race and ethnicity are distinct concepts: an ethnically Hispanic or Latino person can be of any race.

While race and ethnicity are social constructs, ancestry is defined in terms of geography, genealogy, or genetics. The relationship between these three types of ancestry is complex, and can be nonintuitive. Graham Coop has a great series of blog posts illustrating the subtleties around the different types of ancestry. For example, in “How many genetic ancestors do I have?” he illustrates the distinction between the number of genetic vs. genealogical ancestors:

AoURFig2 utilizes the concept of genetic ancestry groups. These do not have a precise accepted definition, but analysis of how the term is used reveals that genetic ancestries labels such as “European” are based on genetic similarity between present day individuals. This is explained carefully and clearly in an important paper by Coop: Genetic similarity versus genetic ancestry groups in as sample descriptors in human genetics.

In AoURFig2 the ancestry groups used are “African”, “East Asian”, “South Asian”, “West Asian”, “European” and “American”. In their Methods section, the authors claim these are based on labels used for the Human Genome Diversity Project, and 1000 Genomes, which specifically they explain in the methods are: African, East Asian, European, Middle Eastern, Latino/admixed American and South Asian (in the figure legend they have renamed “Latino/admixed American” as “American” and “Middle Eastern” as “West Asian”). For each of these labels, obtained via self identified race and ethnicity by participants in the 1000 genomes project, the authors collated their genetic data to obtain genetic ancestry groups. Inherent in these groupings is an assumption of homogeneity, which is of course not true, because the individuals may vary in their genetics and their self identified race and ethnicity may be based on genealogy or geography, which could be at odds with their genetic relatedness to other individuals in their artificially constructed “genetic ancestry group”. Coop makes this point eloquently in his summarizing a key point of his paper:

In summary, there are three notions crucial to understanding AoURFig2: race, ethnicity, and genetic ancestry, each of which is distinct from the others. Individuals who self identify with a particular ethnicity, for example Hispanic or Latino, can self identify with any race. Individuals self identifying with a specific race, e.g. “Black or African American” can be genetically related to a different extent with the six groups of genetic ancestry, and a genetic ancestry group is neither a race nor an ethnicity, but rather a genetic average computed over a set of (mostly genetically similar but also somewhat arbitrarily defined) individuals.

AoURFig2 is shown below. In the following sections we discuss each of the panels in detail.

The figure legend

We begin with the figure legend, which lists Race, Ethnicity and Ancestry. Race and Ethnicity refer to the self identified race choices for participants (based on the OMB categories). Ancestry refers to the genetic ancestry groups discussed above. While these three concepts are distinct, the Ancestry colors are the same as some of the Race and Ethnicity colors:

This is problematic because the coloring suggests a 1-1 identification between certain races and ethnicities, and genetic ancestry groups. In reality, there is no such clear cut relationship, as shown in the admixture panels in AoURFig2 (more on this below). Ideally, the distinct nature of the concepts of race, ethnicity, and genetic ancestry, would be represented by distinct color palettes. The authors may have been confused on this point, because in the paper they write “Of the participants with genomic data in All of Us, 45.92% self-identified as a non-European race or ethnicity.” This makes no sense, because none of the race categories are “European”, and “European” is also not an ethnicity category. Therefore “non-European” does not make sense as either a race or ethnicity category. The authors seem to have assumed that White = European as indicated by their color scheme, and therefore “non-European race” is non-“White”. But by that logic “Hispanic or Latino” = “American” would mean that “Hispanic or Latino” is not “European” which implies that “Hispanic or Latino” is not White, contradicting the specific definition of race and ethnicity categories by the OMB. An individual’s ethnic self identification is independent of their race self identification, and someone may self identify as White and Hispanic or Latino. Clearly the authors would benefit from reading the NASEM report on the use of population descriptors in genetics and genomics research and the NIH style guide on race and national origin.

The ancestry analysis

Panel c) of AoURFig2 presents an ancestry analysis consisting of running a program called Rye on to assign, to each individual, a fraction of each of the genetic ancestry groups. The panel with its subfigures is shown below:

There are several problems with this figure. First, it has no x- or y- axes. The caption describes it as showing “Proportion of genetic ancestry per individual in six distinct and coherent ancestry groups defined by Human Genome Diversity Project and 1000 Genomes samples” from which it can be inferred that each row in each panel corresponds to an individual, and the horizontal axis divides an interval (width of the plot) into proportions of the six ancestry groups. In principle the panels could be in the transpose, with columns corresponding to individuals, but a clue that this is not the case is, for example, the ancestry assignment for Black or African American individuals, presumably none of which turn out to have an assignment 100% to European. That’s just a guess though. It’s best to label axes.

A second problem with the figure is that the height of each panel is the same, thereby not reflecting the number of individuals of each self-reported race and ethnicity. For instance, there are only 237 Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander individuals versus 125,843 Whites. The numbers are there, but the height of the panels suggest otherwise. Below is a bar plot showing the number of people self identifying with each race in the data used for panel c) of AoURFig2:

The All of Us Research Program (henceforth referred to as All of Us) lists as a Diversity and Inclusion goal: “Health care is more effective when people from all backgrounds are part of health research. All of Us is committed to recruiting a diverse participant pool that includes members of groups that have been left out of research in the past.” That is an admirable goal, and while All of Us is to be commended on the relatively large number of self identifying Black or African American participants recruited in comparison to previous cohorts, it’s worth noting that in this analysis White still wins (by a lot).

A third problem with the figure is the placement of the “Hispanic or Latino” ethnicity in the middle of panels assigning ancestry groups to individuals by race. As discussed previously, self identification of ethnicity is orthogonal to race. There is therefore ambiguity in the figure, namely it is unclear whether some of the individuals represented in the Hispanic or Latino plot appear in other panels corresponding to race. The juxtaposition of an ethnicity category with race categories also muddles the distinction between the two.

The ancestry analysis is based on a program called Rye, which was published in Conley et al., 2023. The point of Rye is runtime performance: unlike previous tools, the software scales to UK Biobank sized projects. Indeed, it’s runtime performance is impressive when compared to the standard in the field, the program ADMIXTURE:

However, while Rye is faster than ADMIXTURE, its results differ considerably from those of ADMIXTURE, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5 of the paper:

I haven’t benchmarked these programs myself, but geneticists have some experience with ADMIXTURE which was published in 2009 and has been cited more than 7,000 times. The Rye program, from two groups associated with All of Us, has been cited twice (both times by the authors of Rye who are members of the All of Us consortium; one of the two citations is the paper being discussed here). Of course, one shouldn’t judge the quality of a paper by the number of citations. A paper cited twice could be describing a method superior to a paper cited more than 7,000 times. But I was discomfited by the repeated appearance of a p-value = 0 in the paper (see below for one example among many). It reminded me of pondering p-values before breakfast.

Also R2 is the wrong measure here. The correct assessment is to examine the concordance correlation coefficient. Finally, and importantly, the Rye paper describes results based on inference not with the high-dimensional datatypes but rather a projection to the first 20 principal components. Notably the All of Us paper, and in particular the results reported in AoURFig2, use 16 principal components. There is no justification provided for the use of 16 principal components, no description of how results may differ when using 20 principal components, nor is there a general analysis describing robustness of results to this parameter.

In any case, setting aside feelings of being left Rye and dry and taking the admixture results at face value, it is evident that individuals self reporting ethnicity as “Hispanic or Latino” are highly admixed between European and American (the latter label meaning Latino/Admixed American). This stands in contrast to the coloring scheme chosen, with Hispanic or Latino colored purely “American” implying individuals self identifying with that ethnicity are not European. It also is at odds with the UMAP displays in panels a) and b) of AoURFig2.

UMAP nonsense

The AoURFig2 presents two UMAP figures, shown below. The UMAP is the same in both figures; in the top subplot (a) it is colored by race, and in the bottom subplot (b) it is colored by ethnicity.

The first thing to note about this plot is that it has axes when it shouldn’t. There is no meaning to UMAP 1 and UMAP 2, and the tick marks (-20, -10, 0, 10, 20) on the y axis and (-10, 0, 10, 20) on the x-axis are meaningless because UMAP arbitrarily distorts distances. Somehow the authors managed to put axes on plots which shouldn’t have them, and omitted axes on plots that should. Furthermore, by virtue of plotting points by color resulting in an overlay of one color over another, it’s difficult to see mixture of colors where it exists. This can be very misleading as to the nature of the data.

More concerning than the axes (which really just show that the authors don’t understand UMAP), are the plots themselves. The UMAP transform distorts distances, and in particular, as a result of this distortion, is terrible at representing admixture. The following illustrative example was constructed by Sasha Gusev:

But one doesn’t have to examine simulations to see the issue. This problem is evident in panel c) of AoURFig2. Consider, for example, the Hispanic or Latino ancestry assignments shown below:

The admixture stands in start contrast to the UMAP in b), which suggests that the Hispanic or Latino ethnicity is almost completely disjoint from European (which the authors identify with White via the color scheme). This shows that UMAP can and does collapse admixed individuals onto populations, while creating a hallucination of separation where it doesn’t exist.

I recently published a paper with Tara Chari on UMAP titled “The specious art of single-cell genomics“. It methodically examines UMAP and shows that the transform distorts distances, local structure (via different definitions), and global structure (again via several definitions). There is no theory associated to the UMAP method. No guarantees of performance of any kind. No understanding of what it is doing, or why. Our paper is one of several demonstrating these shortcomings of the UMAP heuristic (Wang, Sontag and Lauffenberger, 2023). It is therefore unclear to me why the All of Us consortium chose to use UMAP, especially considering that they (in particular one of the authors of Rye and a member of the All of Us consortium) were warned of the shortcomings of UMAP a year ago.

Scientific racism

The misuse of the concepts of race, ethnicity and genetic ancestry, and the misrepresentation of genetic data to create a false narrative, is a serious matter. I say this because such misrepresentations have been linked to terror. The Buffalo terrorist who murdered 10 black people in a racist rampage in 2022 wrote that

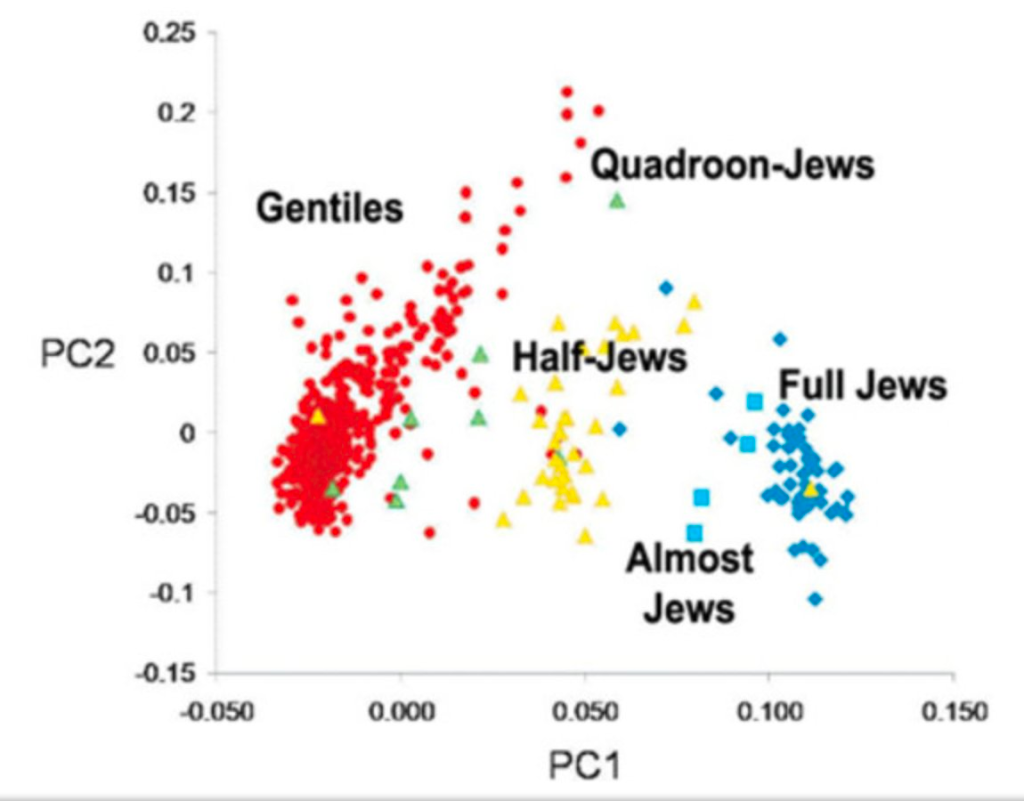

Included in his manifesto, from which this text is excerpted, was the following figure:

This plot is eerily similar to one made by Razib Khan, in which he used the term “Quadroon-Jews” (Khan’s figure was published in the Unz Review, which is a website published by far-right activist and holocaust denier Ron Unz). The term “Quadroon” appeared in the 1890 U.S. Census as a refinement of “Mulatto” (see the first at the top of the post).

These plots show the projection of genotypes to two dimensions via principal component analysis (PCA), a procedure that unlike UMAP provides an image that is interpretable. The two-dimensional PCA projections maximize the retained variance in the data. However PCA, and its associated interpretability, is not a panacea. While theory provides an understanding of the PCA projection, and therefore the limitations of interpretability of the projection, the potential for misuse makes it imperative to include with such plots the rationale for showing them, and appropriate caveats. One of the main reasons not to use UMAP is that it is impossible to explain what the heuristic transform achieves and what it doesn’t, since there is no understanding of the properties of the transform, only empirical evidence that it can and does routinely fail to achieve what it claims to do.

The pseudoscientific belief that humans can be genetically separated into distinct racial groups is part of scientific racism. Such pseudoscience, and its spawn of racist policy, has roots in many places, but it must be acknowledged that some of them are in academia. A few years ago I wrote about the depravity of James Watson’s scientific racism, but while his (scientific) racism has been publicly documented due to his fame, scientific racism is omnipresent and frequently overlooked. The ideas that the Buffalo terrorist and that Watson promulgated are reinforced by sloppy use of terms such as “race” and “ethnicity” in academia, along with misrepresentations of the genetic similarity between individuals. Many of the concepts in population genetics today are problematic. Coop’s eloquent critique of genetic ancestry groups is but one example. The concept of admixture is also rooted in racism and relies on unscientific notions of purity. With this in mind, I believe it is insufficient to merely relegate AoURFig2 to Karl Broman’s list of worst graphs. The numerous implications of AoURFig2, among them the authors’ claim that individuals identifying ethnically as Hispanic or Latino are genetically not European and therefore not racially White (see section on ancestry analysis above for an explanation of why this is incorrect), are scientific racism. The All of Us authors should therefore immediately post a correction to AoURFig2 that includes a clarification of its purpose, and corrections to the text so the paper properly utilizes terms such as race, ethnicity and ancestry. All of us need to work harder to sharpen the rigor in human genetics, and to develop sound ways to interpret and represent genetic data.

Acknowledgment

This idea for this post arose during a DEI meeting of my research group organized by Nikhila Swarna on February 21, 2024, during which Delaney Sullivan presented the All of Us Resarch “Genomic Data in the All of Us Research Program” paper and discussed scientific racism issues with AoURFig2.

5 comments

Comments feed for this article

February 26, 2024 at 1:55 pm

jpatel93

Stellar analysis, I love the depth and focus on corrections.

February 26, 2024 at 2:43 pm

Alex Merz

“There are several problems with this figure. First, it has no x- or y- axes.”

Serious question: who *reviews* these things? Anyone? At all?

February 27, 2024 at 5:49 am

Silvina Montes

True, the same happens with sex. The fact of having XY or XX doesn’t mean at all that you may be a female or a male. It’s basically the same likelihood. Rigtht?

February 28, 2024 at 9:06 am

Kelly

“Bick responds that the manuscript was written in 2022, before the NASEM report was published.” “Rye: genetic ancestry inference at biobank scale, Published online 17 March 2023” They used a tool that wasn’t peer reviewed?

May 5, 2024 at 6:41 am

Camelia

Great analysis. The All of Us program just landed (October 2023) in my homeland Puerto Rico which prompted me to do some reading into it. I’m glad I stumbled upon your article, it confirms the concerns I have with it.